Extend them, says O and grabs the palms of my hands. His fingers are warm and sturdy, the kind that I would somehow expect from a marine engineer born in West Africa. O’s way with words is frugal, but never without a hint of hope; his version of Christianity remains much more personal than the Polish-flavoured Catholicism I grew up in. And while he is saying an uplifting prayer for the success of my trip, I can’t shake off the feeling that only after leaving Ljubljana it is truly starting, the journey I have been really waiting for, with random meetings that will stay with me until senility takes my memory away, with the unexpected and the miraculous waiting around every corner.

Me and O are on the way to Zagreb. We end up seating next to each other because I am a stickler for bus seat numbers. O says he wanted to take a nap, but decided to strike up a conversation with me instead, part of God’s plan, or something along these lines. To try and seek out Jesus in every encountered human being is a dictum repeated ad nauseam in my home country. Too bad it’s rarely put into practice, but here I am, the most unlikely candidate who, on behalf of his countrymen, has a chance to put his money where his mouth is.

And so we talk. The conversation is filled with religious themes, but we also share our stories of how we came to travel in the same direction. O tells me he is doing a day trip before returning to his home in Lagos; I am revisiting the city I hitchhiked to in 2013. Back then me and A had a very able guide, a different A, whom we met via Couchsurfing. Now I am flying solo to catch up on a few museums I didn’t visit twelve years ago.

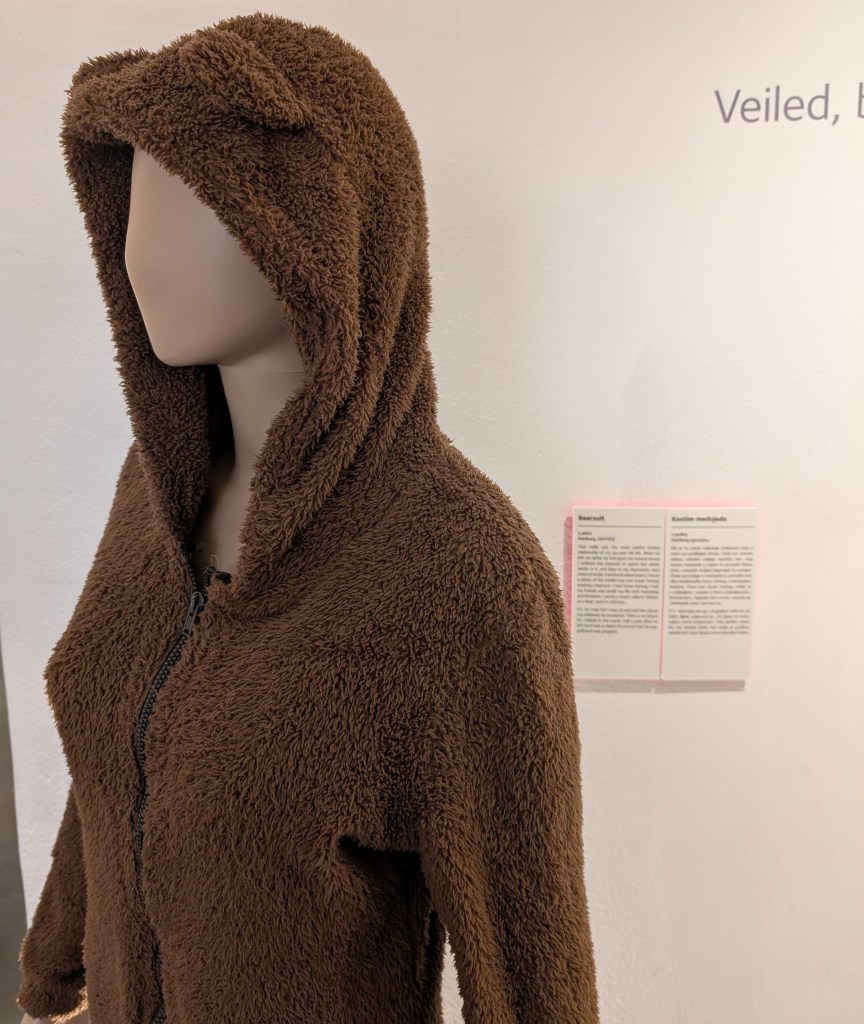

The Museum of Broken Relationships was more relevant to me in 2013. At that time, some deer-and-doe-related heartbreaks were still painfully fresh. Over the years, I have turned from a life of excess to one of abnegation, so right now my love life is a wasteland. I cannot blame anyone but myself for choosing the lifestyle of a vagabond, always passing through, always gone before any kind of attachment can develop. But I wouldn’t have it any other way. The museum is a gift that keeps on giving, because there will never be an end to break-ups, and old exhibits that are merely whitened scars will be supplanted by fresh ones depicting inflamed wounds. There will always be a crowd of people parting with trauma-inducing artifacts and sending them to the museum. A bear suit, a Bob Dylan novel, a Newsweek edition with Barack Obama on the front page, a Holy Mary figurine, they all show loss from a different angle, yet they all converge on the same feeling of helplessness, then the relief of breaking the chains, and finally catharsis.

It’s not just about the romantic aspect of love. The exhibits tell a tale of attachment on every possible level of human experience, wives and husbands, grandkids and grandparents, countries, ideas, dreams, and how they all sometimes get shattered by a strange twist of fate. It is an unabashed contemplation of loss, a deliberate head-on collision with despair, to perhaps make them more familiar, less frightening.

The next stop on my route is another quirky little place, The Museum of Hangovers. A very dangerous concept, and an equally dangerous business plan: the new generations are enchanted more by molly or k-holes than by the good old rotgut. But this is the Balkans, so I buy a small bottle of wine and enter the halls of the museum. The narrative is as trite as it is memorable; who among us never had a liquor-filled expedition through the streets of the city at night, with major blackouts on the way, lost cellphones, found or stolen street signs, strident chanting for or against some football club, friends and enemies made along the way… followed by a rude awakening, a throbbing pain behind the eyes, a parched throat, and a promise to oneself, this was so stupid, never again.

The museum does a great job of explaining alcohol as a cultural phenomenon, but it also doesn’t shy away from giving a few warnings about untrammeled consumption of ethanol. Drunk drivers (eight years in Malta inured me to this phenomenon much dreaded on the continent), negative health impact via increased cancer incidence, accidental loss of life due to overdose or something as silly as falling off a bridge into a cold river, all of these are mentioned, and rightly so. Fortunately, the narrative remains purely informative, not preachy.

At the end, the black receptionist asks if I want to have a shot of rakia; yes, I do, so she pours me one and gives me a staredown while I press the cold glass against my lips. Little does she know, I am a bona fide Slav, so I down it unflinchingly, without so much as a single moment of hesitation. She almost looks impressed.

The next day I decide to stay close to my room, visiting the Nikola Tesla Technical Museum located just around the corner. The day before, when I was prowling the neighborhood where the Museum of Broken Relationships was located, I overheard the genius inventor’s name pop up more than a couple of times. Tesla was a Croat (according to Croats), but he was also a Serb (according to Serbs). The truth is somewhere in the middle, and according to a quote attributed to Tesla, he was equally proud of his Serbian heritage and Croatian homeland.

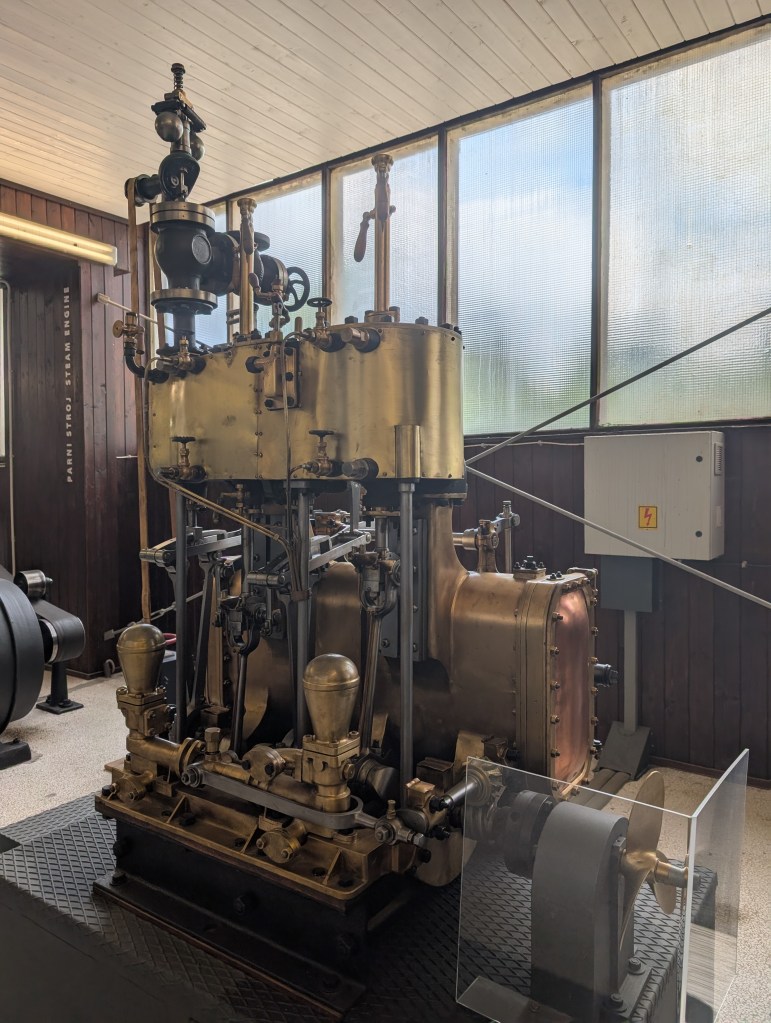

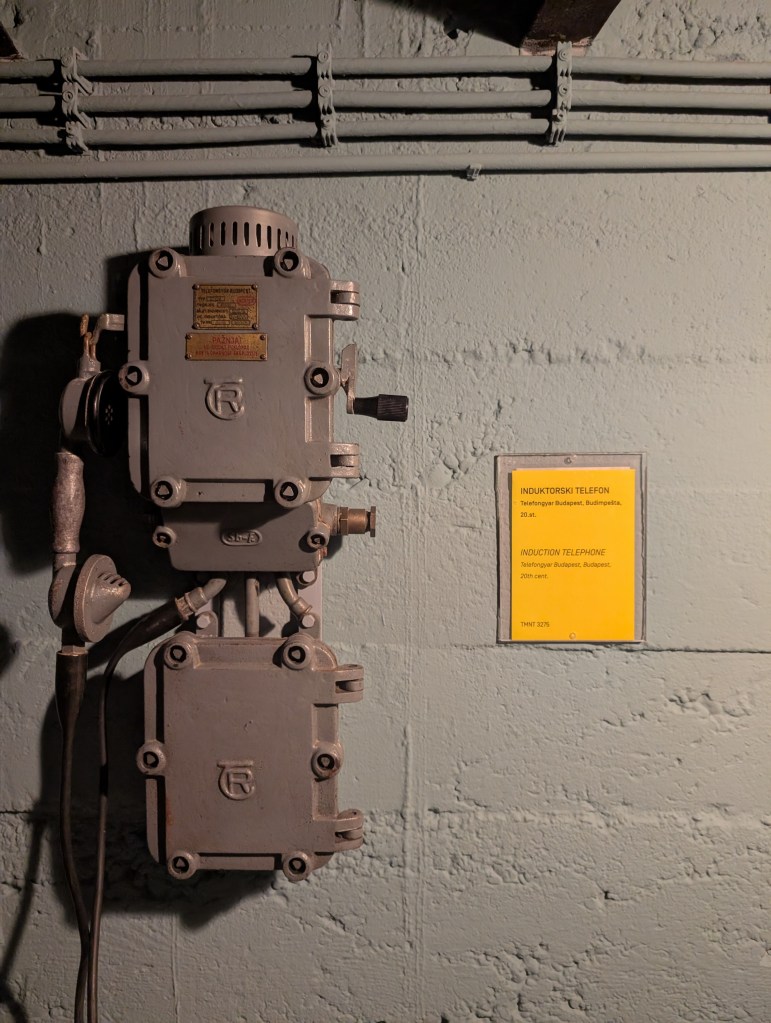

The museum is gigantic, with textual overload screaming at me from every wall. The inside of the building showcases the history of modern science and engineering; it boasts countless exhibits, among them many well-preserved turbines and steam engines, several cars, some planes, a tram, miniature replicas of ships, and, on the upper floor, a collection of everyday items from the Yugoslav era. Old computers, gramophones, ironing boards, fridges, you name it and they’ve probably got it… and much more. Several telescopes and a mini planetarium? Sure. A few bee colonies with plastic tubes connecting the little workers to the world of pollen outside? Of course. A hoe used centuries ago by some Slav farmer? Way ahead of you. And I haven’t mentioned yet a short tour of the coal mine hidden in the basement, or a session where volunteers can become subjects of a few scary-looking scientific experiments involving high voltage and human touch.

The truth is, it’s all a bit too much. I rush through the top floor; if I didn’t, I would spend at least two hours more on top of the four that I have already devoted to the museum. The narrative that I have been hoping for is scattershot, but I reckon some fraying is unavoidable given the sheer size of the place. A different line of thought opens up, and, surprisingly, it features Javier Bardem as Anton Chigurh.

If the rule that you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?

On one hand, it’s related to the speed of technical development very accurately portrayed in the museum. We live in the age of unprecedented technological advancement, but at what cost? The planet is dying, so they say, and no number of steam engines can replace what we’ve already lost. The land is tainted by heavy metals, the waters by microplastics, and we are contributing to mass extinction of species at a scale comparable to an asteroid impact.

On the other hand, more personally, I think about the rule that brought me to Zagreb. All the break-ups, the hangovers, the developments in data science that enabled me to earn easy and fast money. I don’t think I was following any rule, at least not consciously, but here I am, doing what I have always wanted to do. Whatever set of precepts I have been unknowingly following over the years, whatever (non-)deterministic path I’ve been on, it brought me, inevitably, here.

And to have ended up exactly where I am supposed to be is a supreme feeling.

Leave a comment