Where the hell am I?

The main railway station in Athens is exactly what I would expect from late-stage capitalism times we are currently going through. But as I get closer to the city, and eventually leave the subway at the Omonia station, I feel like I got transported to somewhere more eerie, like Baltimore or downtown San Francisco.

There is a man in a hotel bathrobe and flip-flops compulsively scratching his rash-covered calf. He is sprawled on the subway exit staircase and he is manspreading disgustingly, but at least he’s got some underwear on. Up the stairs and into the street…

…where homeless people with diabetic sores are lying half-conscious along the wall. There are some policemen patrolling the streets but long gone are the days when I believed the police were there to help the common people. Their mission is different – it is to protect the capital from any incursion by those barely alive zombies prowling the streets of Omonia. It is to serve as a barricade separating classes, and it is to protect the tourists (quite like myself) who can spend their hard-earned euros on hotels, the Acropolis entrance tickets, or another portion of overpriced and undersized moussaka. Instead of one of the fancy restaurants, I go for the allegedly best budget souvlaki in Greece, located conveniently close to the subway station entrance.

Later I find a hotel along one of the wider streets of the district. Fewer homeless, but the street stinks because garbage collection is not a top priority for the city council. As soon as I hide inside the room, my stomach starts rumbling, so I have to get out again. I find a well-rated grocery store nearby, but the road to it is blocked by a regular shantytown. Rejects, drunks, and addicts all congregate at the corner, a violent and hopeless life where every survived day is a miracle. A young punkish-looking blonde passes me by, a hard-to-interpret smile is dancing on her lips, maybe she’s flirty, maybe she’s using her wiles so that I drop a tenner for a dose of her preferred medicine, or maybe she already got it and mistakes me for another customer in his time of need. There’s a lot of D in her smile, the way I remember her and her street smarts, years ago. I should stay away.

In a nutshell: the first impression of Athens is not very good. Neither is the second.

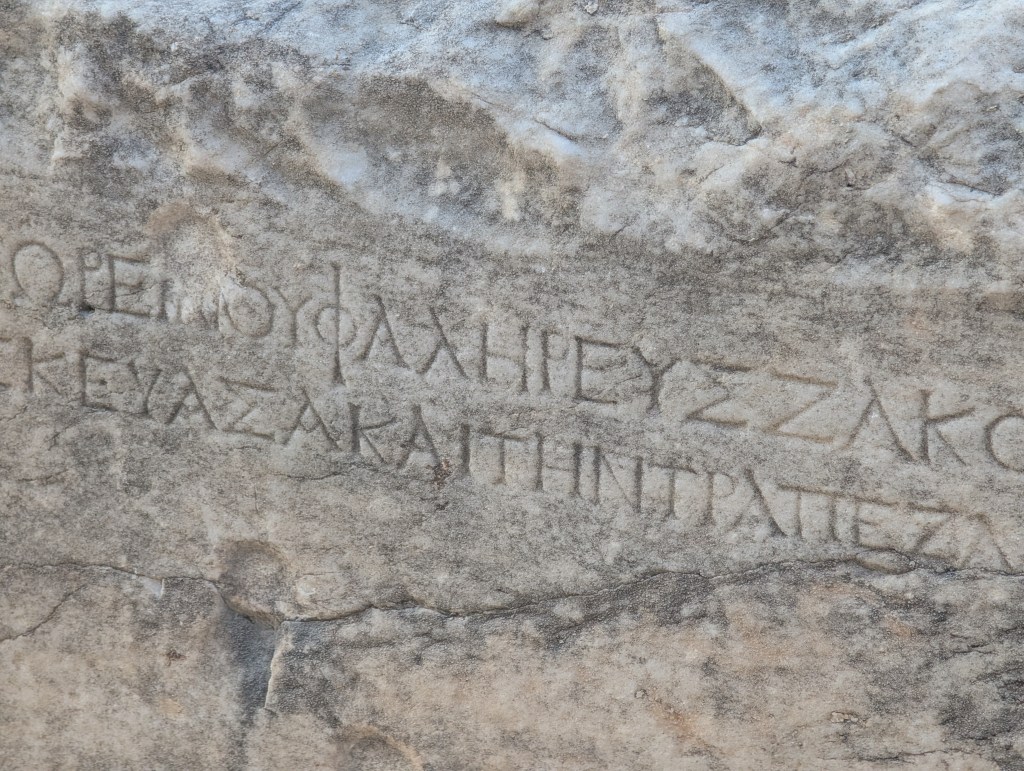

Short on time, I go to the Acropolis. Thirty five bucks to enter, it’s madness. The crowd shuffles in and out as the sun is going down. Don’t get me wrong, it looks spectacular. It is very impressive that it survived a few millennia and was home to so many legendary figures with unparalleled impact on the Western civilization. Pericles, who was perhaps the greatest and only great mayor in history (as stated by Al Pacino’s main character in the 1996 movie City Hall), commissioned the construction of many landmarks that can still be visited today, including the most famous one, the Parthenon.

The crowds are killing me, though. It’s hard to take any good pictures; the little humans set against the ancient columns look like ants. I wouldn’t be myself if I didn’t try, though. From the top, a bit away from the Parthenon, I can see other hills, seemingly less frequented than the most famous one. There is Lycabettus and there is Philopappos, and there are others, all forming the seven hills with which Athens was associated in the past. Cats are roaming the premises; a guard starts shouting at a daring visitor who touched one of the columns; I am rubbing elbows with people of possibly all nationalities and ethnic backgrounds. I am suffocating.

On my way back to the hotel, I use a different exit so I have to walk longer to get to the station. The neighbourhood seems cleaner, the grocery shop is spick and span, but the closer I get to the subway, the more homeless I see – it’s where they usually congregate, hopeless and forlorn, victims of lax monetary policy and the fiscal austerity that followed when Greece was at its limit, back in 2007 and 2008, during the global financial crisis.

Back in the streets of Omonia, I start appreciating the Acropolis area again. The sun is down and I am on my way to the hotel. There is a group of junkies sitting under a lamppost in one of the side alleys; their syringes are filled with brown-colored liquid which, when the plunger is pressed, disappears right into their arms and feet. I momentarily stop and then resume walking. A shudder jolts my entire body. Hopeless cases that will most likely be dead by the end of the year, just like those poor souls at the Wilenski train station in Warsaw.

It’s only been one day and I am done with Athens. My initial plan was to travel to Thessaloniki and then take an overnight bus all the way to Istanbul; it was M, back in Vlore, who made me realize I had loose ends that could come back to bite me in the ass if I didn’t take care of them.

The next afternoon I was going to be back home, my second home. As I looked out the airplane window, there she was, a collection of rocks, my safe haven for the previous eight years.

I was back in Malta.

Leave a comment